skip to main |

skip to sidebar

9:26:00 AM

Unknown

The rapid expansion of Android is seeing a huge number of handsets

running 4.x - but we aren't seeing the expected shift from 2.3, aka

'Gingerbread'. Why?

Something odd has happened to Android.

While

its growth rate continues to grow (yes, a second-order change; sales

are accelerating), we aren't seeing the changing of the guard from the

older version to the newer one that we have over the past two years -

such as the end of 2010, when "Froyo" (version 2.2) replaced "Eclair"

(version 2.1) and then the end of 2011 when Froyo was replaced by

"Gingerbread" (version 2.3).

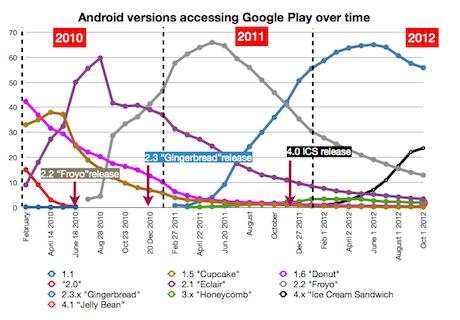

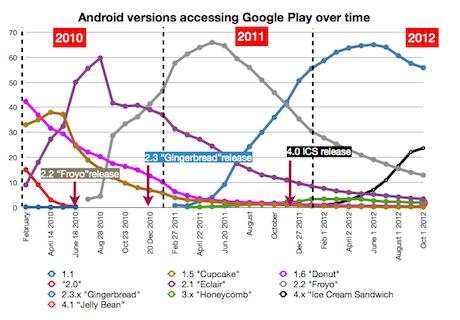

Going by the statistics shown on Google's platform versions

page (which shows the version of Android being used by devices

connecting to Google Play in the two weeks up to 1 October, and is

revised monthly), Gingerbread has been the most-used version of Android

since November 2011. At that point it was running on 42% of devices

connecting to Google Play (then the Android Market), just passing the

40.9% using Froyo.

Versions of Android accessing Google Play to October 2012. Click for larger version. Source: Google, Wayback Machine

As I forecast around the end of last year, this has been the year of Gingerbread:

it has been by far the leading version, peaking in June at 65% of

devices. And now, as has happened in the past, its share is starting to

fall, as the next version, "Ice Cream Sandwich" (4.0, hereafter ICS)

starts to appear on newer devices, and older ones get updated via

carriers.

Can't catch the Gingerbread, man

Except the

difference now is that Gingerbread isn't dropping off as fast as

predecessors. Go back a year: at the start of October 2011, Froyo was

down to a 45.9% share (from a high of 65.9% in May 2011) and Gingerbread

had risen to 36%, and was adding about 6 percentage points every month.

Similarly, by October 2010 Eclair was at 40.4% (down from a high of

59.7% in August) and Froyo was at 33.4%, and adding 4 to 5 percentage

points per month.

Now look at today: Gingerbread is falling, down

from that 65% in June to 55.8% at the start of October - but ICS is at

just 23.7%, and has risen by only a couple of percentage points. True,

if you add in "Jelly Bean" (4.1) then you bump up the 4.x figure to

25.5% . But that's still a long way adrift.

What that adds up to

is that unless something changes quite dramatically in the next couple

of months, Gingerbread will remain the dominant Android version for

quite a while. It's only losing a couple of percentage points per month,

while ICS/Jelly Bean gain about the same. With a 30% gap between the

old and the new variants, it could take another year before things

changed.

Drawing breath

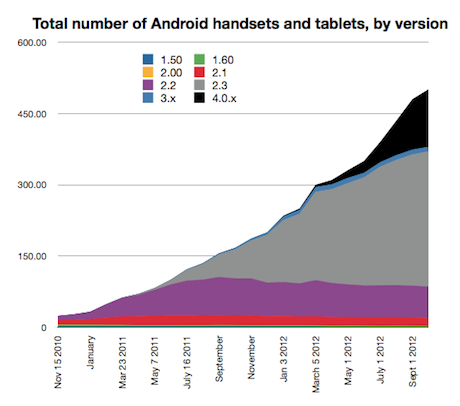

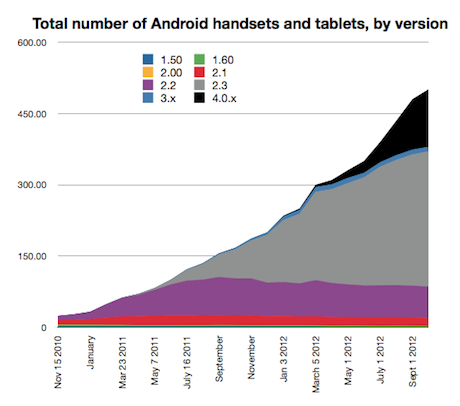

At this stage, we need to make a

few points. First, looking at the numbers in this way masks the enormous

growth in the total number of devices actually accessing Google Play.

The latest figure given by Eric Schmidt, at the start of September, was

480m Android devices. That compares to 190m announced in Google's Q3

earnings on 13 October 2011. So in less than a year, the number of

devices (almost all handsets) has more than doubled.

In turn, that means - if

we accept that the number of devices accessing Google Play is

proportionate to the ratio of devices in the wild (though there's no way

to know that; only Google really knows) - that:

• in October 2011 there were 68.4m devices running Gingerbread

• in October 2012 there were 268m devices running Gingerbread, and 122.4m running 4.x.

In

other words, there are more devices running 4.x now than there were

running Gingerbread a year ago. So even while it might appear that 4.x

(ICS and Jelly Bean) hasn't made much progress, it has - but that's

obscured by the huge growth of Android.

A couple of things to note from those numbers:

• ICS/Jelly Bean went from nowhere to 122.4m in a year

• Gingerbread grew by 200m

devices in the same period, to that 268m figure. It looks like many

manufacturers are still using it because it's a known quantity.

Estimated number of devices running different versions of Android to Oct 2012.

So now there are nearly 360m devices out there which are running versions of Android before

4.x. It's unlikely that a significant number of them will be upgraded;

yes, some might here and there, but it's not actually in manufacturers'

interests to provide an endless upgrade path for Android phones, because

if you keep using a phone, they can't sell you a new one. (Apple offers

long upgrade paths because it sells services on older handsets such as

music and apps,

and those keep people tied into its ecosystem. Android handset makers

don't have the same breadth of services; most of what comes on Android

is via Google, rather than say Samsung or HTC specifically. It's

noticeable that Samsung is making significant efforts to move into

services through extras such as S-Voice.)

What does it all mean?

Gingerbread

isn't going away. About 200m of those handsets are one year or less

old, so they're going to continue for at least another year - possibly

two or three.

ICS/Jelly Bean is growing fast in absolute numbers, but even if a million a day solely

running ICS/Jelly Bean are added, then it will take about 100 more days

before 4.x overtakes 2.3. That's some time in January. However, it's

unlikely that's going to happen - because the numbers suggest that

Gingerbread devices are being added even more quickly than ICS/Jelly

Bean ones.

Again, though, what does that mean? If Gingerbread persists, does anyone lose out?

According to Google, the benefits of 4.x for developers

include a "social API" which can "store standard contact data as well

as new types of content for any given contact, including large profile

photos, stream items, and recent activity feedback", and a "calendar

API" that makes it easier to add calendar services to apps, a visual

voicemail API, Android Beam (for NFC-powered data transfer), "low-level

streaming multimedia" (for DRM-based media), and a whole slew more.

If

you're not using Android 4.x, those aren't available to you, and

they're not available in any apps you might get. Of course, it doesn't

matter to the handset makers, who have got paid by the carriers; doesn't

matter to the carriers, which have sold a phone; doesn't much matter to

Google, which has another customer. So who does it matter to?

Only,

perhaps, to app developers which can't offer higher-grade apps (and so

can't get people to spend more on those new apps); to some of the media

companies which can't take advantage of DRM-enabled streams.; and of

course to users who might have heard about the benefits of ICS/Jelly

Bean, but can't get them because their handset isn't being upgraded.

The

number of devices that get updated, relative to the total number out

there, is likely to be minimal. The reason that Gingerbread isn't

falling away faster is because handsets are still being shipped with it

on (though there's no way of telling, it's possible that many of those

are in China, where Android ran on 80% of the handsets shipped there in

the second quarter).

An update on the Update Alliance

For

those who want an upgrade from Gingerbread to ICS or Jelly Bean, the

situation is much the same as it ever was: it might happen, or it might

not. The Android Update Alliance, announced at Google I/O in May 2011

with carriers including AT&T, T-Mobile, Vodafone, Sprint, and

Verizon, and handset makers HTC, LG, Samsung, Sony Ericsson, and

Motorola, was dead within months. Its promise that "any new Android

phone would receive timely OS updates for at least 18 months following

launch": when PC Mag followed up in December 2011 it was almost entirely ignored, and by June this year Ars Technica found no mention at all.

But in many ways that's not surprising. The figures for US sales of Samsung phones

(released in the Samsung-Apple patent trial in July/August) showed that

phones had a brief life cycle: they'd appear, sell well for a few

months, and vanish, to be replaced by another model.

For the

handset maker and carrier, the hassle of writing and checking OS updates

for a phone that might not even be on sale any more (or if it is has

already been overshadowed) isn't outweighed by any other benefits. It

doesn't bring any extra sales (indeed, it might slow up sales of new

handsets with whizzy new features, because you'd get those features on

the new OS).

Updating certainly brings extra support calls - and

you can guarantee that the number of support calls that follow a new

Android OS update will far exceed the number of support calls before

an update asking where it is. Possibly that's part of the reason why

Motorola has reneged on its promise to update a number of handsets, to the annoyance of users.

If

updating won't bring the handset maker or the carrier any extra money

(and might even cost both), you can see why they'd be reluctant to do

it. Only the pressure of seeing rivals doing so will impel them to do

that - which is where Google, with its Nexus line, needs to be leading

the charge. If it can push out updates, that might drive more updates.

But don't hold your breath, because (as the Samsung trial figures

showed) Nexus devices don't sell in huge numbers; you have to look to

Samsung for that.

So that's the thing about Android. It's getting

so big that the inertia of its existing installed base ihas just begun

to act as brake on the arrival of new OS-based features in the broader

market. While Google wants to push its new products - Google Currents,

Google Now - which require the new APIs, and while those might be

attractive for users, the interests of the handset makers and

carriers's aren't necessarily aligned with them. And this isn't going to

change any time soon.

9:26:00 AM

9:26:00 AM

Unknown

Unknown

9:26:00 AM

9:26:00 AM

Unknown

Unknown

0 σχόλια:

Post a Comment